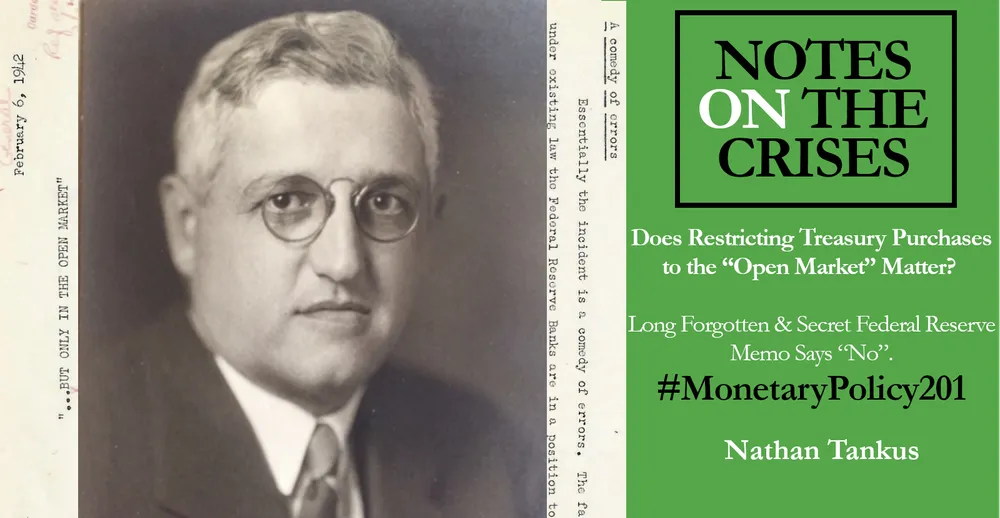

Does Restricting Treasury Purchases to the “Open Market” Matter? Long Forgotten & Secret Federal Reserve Memo Says “No”. #MonetaryPolicy201

#MonetaryPolicy201 is a monthly series about the basics of monetary policy. It’s a “201” series because I will be grounding the basics of monetary policy on their largely forgotten legal foundations. The beginning of this series will focus on various aspects of the question: “What is Money Finance”? This is the Second Part, find Part 1 here. You will need a paid subscription to read the full series. You can subscribe here. Your reader support which makes my Freedom of Information Act project, archival research and general writing possible.

Please recommend an institutional subscription to your academic library, or employer (details here)

In the first piece in the series, we tackled a core part of monetary policy that has previously remained obscure. That is: why exactly can the Federal Reserve swap maturing treasury securities for “new” treasury securities directly with the Treasury, despite the fact that the Fed’s core legal authority to buy treasury securities restricts purchases to the “open market”? What we didn’t discuss was the motivation for that legal prohibition in 1935 and whether that legal prohibition serves a functional purpose. These are important issues because limiting central banks to “open market operations” became globalized after World War Two, becoming a monetary policy “common sense”, which has only come under question in recent years. If we don’t understand the motivations in their own historical context, and what people at the time thought about it, we may be badly misconstruing what matters and what doesn’t.

As it turns out, the answer is that we have been led down a fundamentally wrong path. At least, that’s what a confidential FOMC memo written February 6th 1942 by Emanuel Goldenweiser, head of research and statistics at the Federal Reserve Board from 1925 until his retirement in 1946. It’s not an exaggeration to say that Goldenweiser built the research apparatus, and thus the “brain”, of the Federal Reserve. I plan to write a lot more about Goldenweiser in the future. For now suffice it to say that within the Fed, statements on issues of theory were considered definitive when they came from Goldenweiser. It’s not that no one ever disagreed with him, but by any measure no figure was more respected than him at the time.

Sign up for Notes on the Crises

Currently: Comprehensive coverage of the Trump-Musk Payments Crisis of 2025