The Federal Reserve's Coronavirus Crisis Actions, Explained (Part 7)

Riots, Municipalities and Monetary Policy

This is part 7 of my ongoing coverage of the Federal Reserve’s Coronavirus actions. You can read Part 1 here, Part 2 here, Part 3 here, Part 4 here, Part 5 here & Part 6 here. It feels a little silly to be publishing a technical series on the Federal Reserve’s crisis response while the United States burns from another round of police murdering Black people. On one level, what’s happening has very little to do with the intricacies of central banking. On another level, they are intimately related. Our macroeconomic policy mix is centered around monetary policy and our fiscal safety net has been increasingly ripped apart. Since fiscal policy is a much more flexible tool that can be targeted to specific sectors and groups while replacing and increasing income and wealth, it is the best tool for dealing with discrete social problems and making sure that no one is left behind. The last major challenge to our economic policy mix came in the 1970s when Coretta Scott King co-founded the Full Employment Action Council to advocate for a legally enforceable right to a job. As Coretta said:

When Martin Luther_King, Jr., left us in 1968, he was leading the struggle for jobs and income for every American. Martin Luther King, Jr., understood that the right to sit at a lunch counter is no right at all when you are without a job to pay for the lunch. He knew that the right to_attend a college is no right at all without a job to finance the education. And the right to live in a decent neighborhood is no right at all Without a job to pay the mortgage or rent. Many of the gains of the last two decades are threatened by the disastrous levels of joblessness among mmonty Americans. I fear that the civil rights legislation we struggled for, and some died for, is about to be repealed by the harsh reality of high unemployment and persistent poverty. [...]

I fear that our leaders and people are coming to accept high rates of joblessness as normal aspects of economic life and are becoming insensitive to the enormous human suffering resulting from massive joblessness. We cannot permit this insensitivity and acceptance to spread. It will cost us too much. It costs the jobless dignity and income. It costs our communities dollars and stability. It costs our Nation socially, economically, and morally. Yes; morally, because failure to respond to the needs of the jobless represents far more than lost productivity and wasted talents. It represents a social callousness and neglect which we ought not tolerate. As a society, we must not accept the notion that some will have jobs and income while others are told to wait a few years and to subsist on welfare in the interim. Our democratic form of government can not long survive with two separate societies—one working, one job less; one hopeful, one despairing.

These words largely fell on deaf ears. A major reason why is the 1960s had riots while the 1970s, to the shock of many, did not. Coretta’s organization organized protests and marches but without the perception that the society was coming apart at the seams, federal policymakers didn’t feel the need to act decisively as they had in the 1960s on other civil rights initiatives. In the late 1960s, people began to realize that civil unrest was often a tradeoff of restrictive macroeconomic policy. As the historian David Stein says in his forthcoming paper:

He [A Phillip Randolph] called for a “vast ‘Freedom Budget'” of $100 billion to abolish poverty. And he reasoned that the 'cost may be vastly less than the chance of another Watts [uprising]." Randolph was not alone in making these sorts of calculations. When a Fortune magazine journalist who focused on race and the economy wrote a letter to White House aide Harry McPherson concerning the conference, he confirmed Randolph's analysis. The journalist commented that "in the usual formulation, policy-makers have to balance the desirability of cutting the unemployment rate against the desirability of maintaining price stability: is a one percentage reduction in the unemployment rate, say, worth a two percent rise [in the inflation rate]? [...] The Relevant question .... may... be, is two per cent inflation too high a price to pay to avoid another Los Angeles riot? What I'm suggesting, in short, is that one of the inputs in discussions about monetary and fiscal policy [should] be the implications of that policy for Negro unemployment and employment.”

By the mid-1970s though, riots were not on the horizon despite a major recession. The Ford administration knew this and former officials have explicitly stated how they were emboldened by this fact. Alan Greenspan, who at the time was Chairman of Gerald Ford’s Council of Economic Advisors, explicitly saw a lack of riots as the reason the Ford administration felt emboldened to pursue austerity in order to “beat inflation” (Hat Tip David Stein):

Things were worse than any of us told him was possible. Worse than I would have expected. Nine percent unemployment rate. If any of us had said there would be a 9 percent unemployment rate and the equivalent in Western Europe, and argued that there wouldn't be any significant social unrest in the United States in Europe or Japan, they would have run us out of the country. We went through that period with a remarkable sense of cohesion in the country. [...]

Goerge Meany was advocating $100 billion deficits and a number of things that we all argued might be supportive in the short-run, but with vast long-term costs to the system. We essentially fended them off, and the major reason we were able to do so is that the response to these higher levels of unemployment was remarkably mild. One of the columnists, it may have been Joe Kraft, wrote something on the unemployment situation here and in Europe, noting the great surprise throughout the world at the failure of social radicalism to emerge as a consequence. Essentially that political milieu enabled us to stay fairly well on stream.

In my view, it's important to contextualize monetary policy in this way as these political issues are inseparable from the technical questions of macroeconomic stabilization. Trying to analyze the technical details of monetary policy without this context is at its core an analytical error. People live or die, and uprise or not, based on the macroeconomic and social policy a society pursues. I write about and advocate shifting to a fiscal policy centered macroeconomic policy framework where financial regulation plays a subordinate distributional, and demand restriction, role because I think that framework is the only that’s up to the task of responding to climate change and the deprivation that’s leading to civil unrest.

That framework may seem unrealistic and far away, but social instability tends to make the seemingly unrealistic possible. The New Deal was unimaginable in the years before it happened- and so was reconstruction. For those of you who are just interested in the technical Federal Reserve details, I will continue to provide them (as the rest of this post will do). But my larger political takeaway is the same. As purchase and sale policy gets more heavily used by the Federal Reserve, and it has politically more obvious distributional consequences between business, state and local governments and households, Federal Reserve policy will become much more popularly political and the only way out of that uncomfortable position for the Fed is becoming a subordinate junior partner to new fiscal policymaking agencies and Congress.

With that, I’m going to move onto the series itself. I haven’t written about the Federal Reserve’s Coronavirus crisis actions since the beginning of May. Partially, that is a result of wanting to focus on other issues. However, it largely comes from the fact that the Federal Reserve hasn’t announced all that much. Below I cover just 6 Federal Reserve announcements, and I felt I was stretching to justify covering 1 or 2 of the announcements below. The big announcement from this month, which is mainly a negative one, is the update to the Municipal Liquidity Facility which made it far more restrictive than many had anticipated. It feels like a painful irony that I’m writing about this just as a major metropolitan area erupted. With that said, it's time to dig into the minutiae ...

May 5th

That Tuesday, the Federal Reserve joined the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation to tweak one of the major liquidity regulations to come out of the financial crisis. Specifically, they are adjusting how The Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility and the Payroll Protection Program Liquidity Facility loans are treated by the Liquidity Coverage Ratio. Recall the definition I provided for the Liquidity Coverage ratio in the very first post in this series:

The major one, Liquidity Coverage Ratios (LCR) applies to banks with more than 250 billion dollars in assets or more than 10 billion dollars of potential exposure to movements in foreign exchange rates. It says that these banks have to have enough “high quality liquid assets” to meet 30 days of net payment outflows (money immediately coming in minus money immediately coming out) based on a “stressed” scenario. The “Tier one” High Quality Liquid Assets (HQLA) are treasury securities and settlement balances.

With that definition in mind, let’s examine this rule change. It's worth quoting directly from the Federal Register notice. Incidentally, I should mention that the Federal Register notices on announced administrative rule changes tend to have some of the best official government analysis of the macroeconomic situation and it’s worth reading them occasionally to get a sense of how regulators are thinking about such issues. In this case, I think the Federal Register notice is particularly good:

Absent the interim final rule, under the LCR rule, covered companies would be required to recognize outflows for MMLF and PPPLF loans with a remaining maturity of 30 days or less and inflows for certain assets securing the MMLF and PPPLF loans. As a result, a covered company’s participation in the MMLF or PPPLF could affect its total net cash outflows, which could potentially result in an inconsistent, unpredictable, and more volatile calculation of LCR requirements across covered companies.

Under the LCR rule, secured loans from a Federal Reserve facility with a remaining maturity of 30 calendar days or less are categorized as secured funding transactions with a sovereign entity and assigned an outflow rate that varies based on the collateral securing the loan. In addition, the LCR rule assigns inflow rates to collateral generally based on the asset and counterparty type. As a result of the applicable inflow and outflow rates in the LCR rule, MMLF and PPPLF transactions could receive a non-neutral liquidity risk treatment. Moreover, after these loans are extended and upon their maturity, the associated inflows and outflows could unnecessarily contribute to volatility in LCRs.

Under the terms of the MMLF and PPPLF, covered companies use the value of cash received from posted or pledged assets to repay the MMLF or PPPLF loan, respectively, and in no case is the maturity of the collateral shorter than the maturity of the advance. In addition, because the advance from the Federal Reserve Bank is non-recourse, the banking organization is not exposed to credit or market risk from the collateral securing the MMLF or PPPLF loan that could otherwise affect the banking organization’s ability to settle the loan. For these reasons, the agencies believe that it is appropriate to provide predictable and consistent treatment for participation in the MMLF and PPPLF by neutralizing the effects of participation in the MMLF and the PPPLF on covered companies’ LCRs.

Let’s unpack this. Basically what the regulators are saying is that the Liquidity Coverage Ratio’s formula assigns essentially an outflow risk based on the origination of these loans and a “lack of inflow” risk based on these assets which are inconsistent with the structure of the Federal Reserve facilities. Most notably the Liquidity Coverage Ratio, despite being a liquidity regulation, doesn’t have a mechanism for recognizing when newly acquired assets are “maturity matched” with newly issued liabilities. They are also saying that inflows are basically guaranteed because the loans are no recourse so that the collateral can just be handed to the Federal Reserve at any time. The term finance point is particularly important and suggests the whole design of the regulation is flawed. There should absolutely be preferential liquidity treatment for maturity matching assets with comparable liabilities. In fact, my colleague Rohan Grey’s proposal for shifting us away from liquidity regulation is for all bank loans to be automatically pledged as collateral at the discount window with term loans whose maturity matches the collateral. In this respect, this crisis makes a good case for his proposal and makes our current suite of liquidity regulations look … less than ideal.

May 8th

That Friday, Financial regulators put out a joint policy statement on “allowances for credit losses and interagency guidance on credit risk review systems”. When I first clicked on this press release, I assumed it would be Coronavirus related. Instead, it's the result of a much longer regulatory process that’s been under way for a while. As such, I’m not going to highlight specific elements of it. What’s notable is a) how much of the administrative capacity of the financial regulatory state has been devoted to this activity during the crisis and b) that they aren’t updating these standards for the crisis, at least not yet.

May 11th

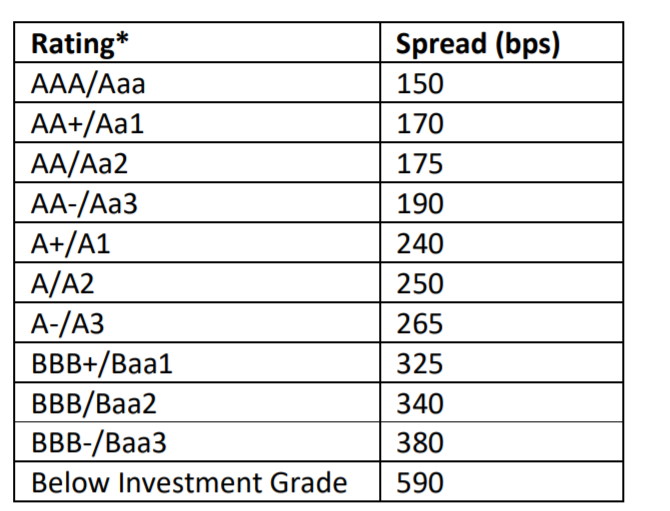

That Monday, the Federal Reserve announced an update to its Municipal Liquidity Facility. The central problem with the update is the pricing of the facility. The pricing is onerous, especially punishing municipalities and states judged less credit-worthy by private credit rating agencies. They are charging a 5.9% premium above short term interest rates to below investment grade municipalities. Even triple A rated securities are being charged a 1.5% premium. In addition, there is a .1% upfront“origination fee” for using the facility. Cities and States are unquestionably public infrastructure. Conventional private sector criteria such as credit-worthiness should not be how a program administered by a federal agency is managed during a crisis when lives are on the line. This prohibitive pricing will limit the use of the facility and hamper the Federal Reserve’s crisis response. The Federal Reserve needs to let go of the stingy instinct it has when it comes to sub-federal governments. I’d argue they should be doing the complete opposite thing. Use 14.2(b) “non-emergency” authority to establish unlimited credit lines for every state & local government. The limiting principle should be not their creditworthiness or potential deficit, the limiting principle should be the previous year’s discretionary budget. Let the automatic portions of state and local budgets function as automatic fiscal stabilizers are intended to function and simply limit how much they can increase discretionary spending or cut taxes. This is the proper way to use them as instruments of monetary policy- and to respond to the crisis on the scale it demands. Reversing this decision should be the main demand of any politician, political group or activist who wants to avoid a prolonged and painful depression and want a “life-saving” monetary policy

May 12th

That Tuesday, the Federal Reserve updated the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF) with new information on which borrowers, and the eligible collateral. This seems to be a result from political fallout. The new facility is more restrictive, especially with regard to the international distribution of the borrower’s employees. The borrower must have “have significant operations in and a majority of their employees based in the United States”. What types of assets which qualify have also been restricted. The announcement also states that this facility, as well as the Payroll Protection Program Liquidity Facility, will disclose detailed information about their activities, including the borrowers, on a monthly basis. I generally think that’s a good thing.

May 15th

That Friday, the Fed, the OCC and FDIC put out another statement “tweaking” federal regulations, this time the “Supplementary Leverage Ratio”. This is essentially the rest of the financial regulators ratifying the decision taken by the Federal Reserve, as it independently made this decision on April 1st. Since I covered that action in Part 4 of this series, I’m simply going to repost my comments from then:

This change is attempting to move the Fed away from that market making role by ensuring that private actors absorb treasuries as needed. In addition, the rule also excluded settlement balances held in accounts at the Federal Reserve from the supplementary leverage requirement. This is important for slightly different reasons. The Fed doesn’t have to worry about banks not accepting settlement balances in payment. Instead, the worry is that Federal Reserve actions which increase the banking system’s level of settlement balances will force them to reduce other activities.

In this way, Federal Reserve lending to and purchases from non-bank entities could actually reduce bank lending by taking up balance sheet space and moving financial institutions closer to the asset ceiling set by supplementary leverage ratios. Excluding balances held at the central bank prevents this phenomenon. Other central banks have done this kind of thing in normal times. This is another change that is bound to lead to the question “if it's good enough for a crisis, why isn’t it always good enough?” Leverage ratios that exclude government guaranteed assets, unlimited intraday liquidity and a freely open discount window is a radically different policy suite that should be considered in “normal” times. Unlike now, normal times may require stricter asset-based financial regulations, but that is a feature not a bug.

May 20th

That Wednesday, there was another interagency statement providing “principles for offering responsible small-dollar loans”. The announcement states that it's a follow up on an announcement from March 26th. The essence of this statement is to emphasize that small dollar loan programs would need adequate loan underwriting, no discrimination, reasonable rates and involve successful repayment by a “high percentage of customers”. It’s not clear how such programs could be designed to accomplish such goals during this crisis and provide emergency credit to households in need during this crisis. It is also unclear how this policy is consistent with loan forbearance which financial regulators are encouraging in other circumstances. To me, this policy fundamentally reflects a failure of our cash payment programs and infrastructure. Direct payments to individuals should be providing the “bridge funding” that expansions of small dollar lending programs are meant to help with.

Conclusion

As the crisis seemed to ease overall, the Federal Reserve has slowed down its crisis response. That’s understandable. They are working hard to implement the programs they have already announced. What is not reasonable or understandable is how they have hampered the Municipal Liquidity Facility. They need to completely reverse their attitude to this policy tool. If they don’t forcefully make the case that another administrative agency needs to be empowered to provide Congress with expertise on fiscal policy and ultimately, to conduct some degree of discretionary fiscal policy, this will be the only tool left in their toolbox. The alternative policy, that of increasing corporatist coordination and planning, will not do well in this political climate. I’m curious to see how the Federal Reserve will respond to the riots, especially in the upcoming Humphrey Hawkins hearing. That’s all for tonight! Stay safe everybody.

Sign up for Notes on the Crises

Currently: Comprehensive coverage of the Trump-Musk Payments Crisis of 2025