“The First Cause of Stability of Our Currency is the Concentration Camp”: Central Banker Solidarity on the road to Hitler’s Czechoslovakian gold

Pavlos Roufos is a Greek political economist living in Berlin. He has a PhD in political science from Kassel University. He works on central banks, constitutional law and European integration from the 1920s to today, with a special emphasis on the Eurozone crisis. You can find his newsletter "The End of Times" here

Editor’s Note: Hello, Nathan here. I’m publishing this guest piece as part of a larger interest in the politics of central banking, especially the politics of central banks as fiscal agents. Next week I will be launching a premium “#MonetaryPolicy201” series that will start with a set of legal issues in the 1930s. In 2025 I will be writing more about 1930s and 1940s “fiscal agent” politics at the Federal Reserve. Since my focus is primarily on the United States, it's helpful to get expert perspectives on related histories from other countries. None, of course, are as charged as the history of Nazi Germany. Thank you to Pavlos for writing this fascinating article for Notes on the Crises

In the autumn of 1938, an internal memorandum was circulated among Reichsbank officials about the dire economic situation of Nazi Germany as a result of the frenzied rearmament policy through central bank monetary expansion. Warning against its inflationary effects, the memo suggested a “smooth landing” from a war to a peacetime economy. In the following months, seeing that instead of restraint there was a further acceleration of the armament race, Reichsbank President Hjalmar Schacht and the banks’ directorate decided to issue an official memorandum, which Schacht delivered directly to Hitler’s hands. Emphasizing that the Fuhrer himself had always “rejected inflation as stupid and senseless”, the letter stressed that “Reichsbank gold and foreign exchange reserves were ‘no longer available’”, that the trade deficit was “rising sharply” and that “price and wage controls were no longer working effectively”. With the volume of notes in circulation accelerating, state finances were bluntly described as “close to collapse”. (Marsh 1992: 119; Mee 2019)[1]. As the memorandum stressed,

…the unlimited increase in government expenditure defeats every attempt to balance the budget, brings the national finances to the verge of bankruptcy despite an immense tightening of the taxation screw, and as a result is ruining the central bank and its currency. There exists no recipe, no system of financial or monetary techniques – however ingenious or well thought-out – there is no organisation or measure of control sufficiently powerful to check the devastating effects on the currency of a policy of unrestricted spending. No central bank is capable of maintaining the currency against an inflationary spending policy on the part of the state.

Hitler did not appreciate the objections. After all, Schacht was the wizard central banker who had come up with the Mefo Bills, an ‘ingenious and well thought-out’ plan (Tooze 2006: 54).[2] Hitler was also not particularly concerned about inflation. As he had already explained to Schacht “[...] the first cause of stability of our currency is the concentration camp: the currency stays stable, when anyone who asks higher prices is arrested.”.[3] According to some testimonies, after he read the Reichsbank memorandum, Hitler “fell into rage” demanding that Schacht be relieved of his duties, alongside two more Reichsbank officials.

The 1939 memorandum was not critical of the rearmament process, or the military intentions behind it. Hitler was already committed to expanding Germany’s Lebensraum through military action and all state officials were fully aware of that. What the Reichsbank President and directorate members such as Karl Blessing and Wilhelm Vocke expressed was their opposition to what they saw as bad economics.[4] In their postwar testimonies both Schacht and Vocke would claim that the tone of the letter was chosen deliberately in order to ensure their dismissal from the bank. Given that these testimonies appeared when building anti-Nazi credentials was a question of survival, one can take them with a pinch of salt. In any case, Schacht was dismissed (though he remained a Minister without portfolio - Reichsminister) while Blessing and Vocke, who were not mentioned in Hitler’s dismissal order, resigned one month later.

Officially, Hitler’s actions after the memorandum ended the independence of the Reichsbank and has post facto served as evidence of opposition to the Nazi regime by Reichsbank officials. As Simon Mee has shown, however, the so-called ‘independence’ of the central bank had already been ended by a 1937 law[5] — which was itself a merely legal affirmation of changes that had taken place with Hitler’s 1933 rise to power.[6]

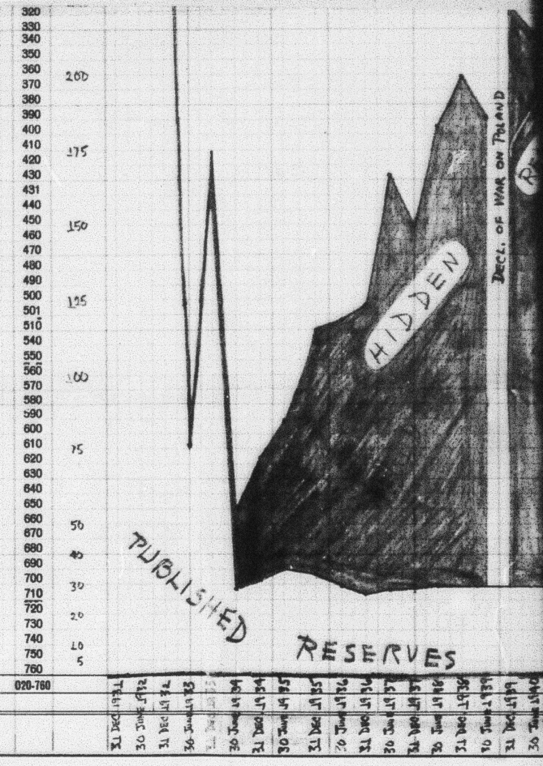

During that period, and among his achievements as “money wizard”, Schacht had created an elaborate system for hiding gold reserves from the official balance sheets of the Reichsbank by placing them in five special accounts created for the purpose. Postwar testimonies of Reichsbank officials claimed that Schacht’s plan for the hidden account was to save enough gold reserves for supporting a return to a ‘free market’ economy. The same officials also claimed that after Goering was informed about the account in 1938 he started using it as a ‘war reserve’ - contrary to Schacht’s wishes. But a more informed statement by Emil Puhl,[7] vice-president of the Reichsbank between February 1939 and May 1945, admits that the special account was known as the ‘war reserve’ already by 1937, when Schacht was still president.[8] Contrary to his later testimonies, this hidden gold reserve was used for the purposes of re-armament until 1939. Finally, balance sheet statements recovered by American officials show that this ‘hidden reserve’ continued to be utilised at least until 1942.

Page from the recovered balance sheet statements of the Reichsbank highlighting the hidden gold reserves.

Declassified E.O. 12065 Section 3-402/NNDG, No. 775059

The 1939 dismissal of Schacht from the Reichsbank had not, despite his various excuses to his interrogators in the postwar period, ended his collaboration with the Nazis. Appointed “Reichminister without portfolio” in Hitler’s cabinet straight after his dismissal, he continued receiving wages from the Reichsbank until 1942.[9] Moreover, both Schacht and Vocke, their commendable dismissal/resignation notwithstanding, had routinely signed orders to financially persecute Jews directly contributing to all financial measures that were part of the process of “Aryanization” of the economic sphere. If there is a difference between them, it concerns Schacht’s continued engagement with the Nazi regime as opposed to Vocke’s complete withdrawal from public life.

Blessing purported opposition to Nazism carries even less evidence. While some accounts claim that he had little time for the Nazis, Blessing had already joined the NSDAP in 1937 (around the same time he had joined the Reichsbank) and had participated in conferences organized by the central bank as a party member. He was, for example, present in the “Conference on the Jewish Question” that took place two days after the Kristallnacht in 1938 at Goering’s Ministry, a meeting tasked with “...formulating specific steps to be taken to insure [sic] the complete elimination of Jewish participation in the economic and social life of Germany”[10]. Even more damning was the fact that after leaving the Reichsbank, Blessing hung out with Himmler and his Freundekreis (Circle of Friends), a group of elite industrialists and SS members.[11] In the company of this select group of pleasant people, Blessing took part in Himmler’s guided tours to Dachau (1937) and Oranienburg (1939). Like many other initial National Socialist sympathizers, Blessing would eventually find himself in the ranks of the conservative opposition to Hitler which conspired for the assassination attempt of July 1944. While this act has received memorable reports and glorification, it is often forgotten that many of the conspirators were conservative reactionaries with deep anti-Semitic beliefs who were essentially horrified by the prospect of military defeat, and further humiliation (second within three decades) of the Germany army. As reports by US Military Authorities on the composition and intentions of this group show, another strong motivation was to reach an agreement with the Western Allies, in order to collaborate against the Soviet Union. According to his own testimony, Blessing escaped his execution after the July 1944 assassination attempt due to the direct intervention of then Reichsbank President, Walther Funk.

During the postwar Nuremberg trial, Schacht was charged with funding the re-armament process and ‘preparing the war’ for Hitler. As the documents of his interrogation by Allied forces in July 1945 show, he defended himself by claiming that after 1938 he refused any discounting requests addressed to the Reichsbank (because he was “opposed to the war”), while also repeating the claim that the 1939 memorandum was an excuse to leave the central bank. Pushed by his interrogator, however, he admitted that the Nazi state continued to function, in part, through issuing government securities which crucially relied on the Reichsbank as a “fiscal agent”.[12] At the time, none of that convinced his interrogators, so he was shown the way to Nuremberg.

Already serving as president of the directorate of the Bank deutsche Länder — the postwar precursor of the Bundesbank created to oversee the currency reform of 1948 —, Wilhelm Vocke served as a Schacht’s witness at Nuremberg. His main line of defence was to repeat the claim that the 1939 memorandum was an act of anti-Nazi resistance and a “mutiny” against Hitler. According to his lawyer, Schacht was a “martyr to the ideals of a sound currency”. As Mee notes, it was this portrayal of the memorandum by both Schacht and Vocke that convinced the Nuremberg judges to acquit Schacht of all charges. But its uses went beyond ensuring Schacht’s acquittal in Nuremberg. For it was at that precise moment that one of the most persistent mythologies of postwar Germany was born, that of associating the pursuit of “sound finance” by independent central bankers with resistance to Nazism.

Rather than a counterforce against authoritarianism, the doctrine of central bank independence (CBI) promotes the conceptualisation of inflation and political interference as cardinal sins, against which authoritarian (or even military, as we shall see) actions are seen as acceptable. This fact becomes visible in another, largely forgotten, episode of that period which links the Reichsbank, the Nazi invasion of Czechoslovakia and confiscation of its gold reserves, BoE’s Governor Norman and the Bank of International Settlements (BiS). And it brings us back to 1939, around the time of Schacht’s dismissal from the Reichsbank.

“Aryanizing” Central Bank Independence

Montagu Norman, Deputy Governor of the BoE from 1918 to 1920 and Governor until 1944, is correctly credited as one of the first central bankers to promote the concept of central bank independence already from the early 1920s. Initially motivated by personal considerations in relation to the BoE and the various national banks of the British Empire and the Dominions, Norman quickly became an advocate of CBI per se and a tireless proponent of the creation of an epistemic community of central bankers structured around their independence from political/democratic interference.[13]

Aware that beyond central banking practitioners CBI remained an institutional form for which, according to Norman, “there is no text book”,[14] he had put his full weight behind Kisch & Elkin’s 1928 Central Banks: A Study of the Constitution of Banks of Issue, the first ever attempt to spell out a theoretical doctrine of CBI. Regarded as “a book on a new subject” (Hawtrey 1928)[15], Norman considered the issue so important that he overcame his reluctance to make public interventions and took it upon himself to write the book’s foreword. There, he remarked that

With the outbreak of war in 1914 the traditional practices of Central Banks were gradually abandoned under the pressure of political expediency. The following years of peace saw the scope of some existing Central Banks altered and new institutions established, and with the return of more normal conditions questions arose regarding the rightful functions and powers of Central Banks in general. Thus it became necessary to consider precisely what rules and statutes should be adopted for the purpose either of limiting or of increasing the respective powers of such Banks.

Already from 1921, in a manifesto circulated (and received with great approval) by central banking peers such as Benjamin Strong of the Federal Reserve, Norman noted with doctrinal persistence that “a Central Bank should be independent”.[16] Such an unequivocal belief in CBI was directly connected to a strong distrust of ‘politics’ and a self-understanding of central bankers as a separate ‘caste’ of technocrats who “had more chance than any politicians of guiding the peoples of the world, both nationally and internationally, in the adoption and maintenance of policies needing time and patience”.[17]

Norman and Schacht shared this aversion towards central banks being “constantly hampered by the political authorities” (as the latter would put it),[18] developing a very close personal friendship as early as 1926. We thus learn from Morgenthau’s diaries, for example, that when Schacht was sent to London in December 1938, officially tasked by Hitler to reach an agreement about plans to fund the forced expulsion of Jews through ‘German’ funds (expropriated property of Jews) and international funds (through the Intergovernmental Committee for Refugees set up by the US), Schacht used the trip “to capitalize one of his remaining assets, namely, his connections with and acceptability to the Bank of England and the British financial community” in order to strengthen his increasingly weak position inside Germany. More than happy “to make a show of the community of central bankers” (Morgenthau Diaries, Book. 159, p. 69), Norman would reciprocate with a visit to Berlin in January 1939, taking the opportunity to fulfill his “long standing promise [to] become godfather to Schacht’s grandchild” (Ibid).

As noted, Norman’s full-fledged solidarity with Schacht went beyond their personal friendship. It was primarily reflective of his anti-inflationary priorities and the strong conviction that only independent central bankers could be effective against political interference brought about by “the gradual extension of the franchise and the reform of electoral systems [...] growing unionisation, the rise of political parties dominated by the working classes and the growing attention paid to the problem of unemployment”[19].

In the case of Nazi Germany, it was seen as a means of minimising inflationary pressures in the German economy and Hitler’s protectionist and state-planning tendencies. As such, it was also fully consistent with Norman’s conviction about the need for a policy of appeasement towards Nazi Germany (Morgenthau Diaries, Book 159, p. 275) and his awareness of Schacht’s active role in the process of ‘Aryanization’ of the Reichsbank,[20] the expropriation of Jewish property and the forced expulsion of Jews. Lastly, it was also in full knowledge of Nazi expansion plans in Central Europe, which Norman saw as “inevitable”.[21]

Such gestures of central bankers’ solidarity would not, in the end, help Schacht retain his position in the Reichsbank - although, as mentioned, he remained a member of Hitler’s cabinet. Norman would be disappointed, relaying one month after Schacht’s dismissal that he considered him his most important source of knowledge about Germany “for the last sixteen years” (Morgenthau Diaries, Book 166, p. 104), further noting that Schacht’s firing raised concerns “over the question of business morality”. “If the capitalist system is to survive”, he added, “that must be improved” (Morgenthau Diaries, Book 164, p. 324).

Replacing “The Old Wizard” With New Gold

Schacht’s replacement – Walther Funk – might have been a loyal Nazi, but he was hardly equipped to deal with the mounting economic problems.[22] In his meetings with other central bankers at the BiS, insisting that he intended relations between the Reichsbank and the BiS to remain unchanged despite the initial shock after Schacht’s dismissal,[23] he also showed that his approach to economic and monetary issues relied on Hitler’s dictums. In a telegram sent to U.S. Treasury Secretary Morgenthau on March 14th 1939, for example, we learn that Funk declared that although

he intended to follow Schacht’s policies [...] it might be found desirable to change the Reichbank’s legal form to make it more definitely a constituent part of the totalitarian state. Inflation he said was inconsistent with the idea of an authoritative [sic] government, and there would be no inflation in Germany.

Since, therefore, changing economic and monetary policy within Nazi Germany was out of the question, other options dominated the attempts to secure Nazi finances. One of them: the confiscation of the gold of invaded countries. There is little doubt that the Reichsbank’s hidden accounts were used to store the expropriated gold from invaded countries like Czechoslovakia or Poland. Yet, before the gold could reach the Reichsbank and be directed towards ‘special’ accounts or sold to acquire foreign exchange, another mediation was necessary. For this to take place, however, no Nazis were needed. Just central bankers.

A few days after the invasion of Czechoslovakia of March 15th of 1939, the chief cashier of the Bank of England (BoE) received an unusual request from the Bank of International Settlements (BiS)[24]: he was asked to transfer £5.6 million in gold from the No. 2 account to the No. 17 account. It so happened that the BoE did not only already have a banker-customer relationship to the BiS but the nominated Director and Chairman of the Board of the BiS at the time was Otto Niemeyer, who was also the executive director of the BoE.

When the request to transfer the gold from Account No. 2 to Account No. 17 was made, the BiS knew well that it was essentially asked to transfer gold from the Czech National Bank Account (No. 2) to the Reichsbank’s account (No. 17). While in full knowledge that this was gold seized by the Nazis after their invasion and occupation of Czechoslovakia, there was zero hesitation. The gold was transferred on the same day.

The news of the transaction, as well as the ones that followed it, caused a stir around Europe. But when the Governor of the Bank of France called the BoE’s Governor, Montagu Norman, complaining and urging him to organise a joint protest against BiS president Johan Beyen,[25] Norman dismissed his outrage. Speaking as a central banker, he responded by evoking the need to retain the independence of the BiS from ‘political influence’. As he was reported remarking: “it would be wrong and dangerous for the future of the BiS … to attempt for political reasons to influence the decisions of the president.” (BoE, p. 1294).[26]

From a telegram sent to Morgenthau in early June 1939, however, we learn that a German delegation had gone to London in order to negotiate issues such as Czechoslovakia’s gold held at a BiS account in London and the blocking of other Czechoslovak deposits by Britain (out of fear that Czechoslovak debt to Britain would not be repaid, as had happened with Austria). While British officials made it clear that their debt claims would be repaid, if need be by seized Czech assets, the same report to Morgenthau says that the German delegation had received assurances “from the British Government” (and not just the BoE) that “that no objection would be raised to withdrawal by the Bank for International Settlements of six million pounds which it had on deposit in London for the account of the Czech National Bank and turning it over to the control of the Reichsbank.” (Morgenthau Diaries, Book 193, June 1-3 1939, p. 1/136).

Advised by Norman, Chancellor Chamberlain responded to questions about the Czech gold in the House of Commons by referring to the terms of the Brussels protocol of 1936 and its ratification in 1937, signed by the BoE. That provision, he noted, forbade “taking any steps by way of legislation or otherwise, to prevent the Bank of England from obeying the instruction given to it by its customer the Bank of International Settlements to transfer gold as it may be instructed”. (Ibid, p. 1293)

Any further attempts to obstruct the transfer of gold from occupied Czech territories to Nazi hands, and thereby legitimise its expropriation, were met with the same response. After Chamberlain insisted to Norman that the pressure he received was becoming too hard to handle, Norman insisted on the importance of not changing course. “The questions”, he wrote to Chamberlain, “by certain members of the House of Commons do not change my views on, nor my attitude towards, the Bank of International Settlements. I do not, therefore, propose in any way to modify the line of conduct [...]” (Ibid, p. 1295)

Post facto excuses for Norman’s attitude by the BoE would claim that his main aim was to “keep the BiS alive to play its part in the solution of post-war problems” (Ibid). But these appear more as postwar excuses rather than facts. We know, for example, that these debates took place in the summer of 1939, before the invasion of Poland. At the same time, as we learn from the Morgenthau diaries, hardly anyone believed that total war was approaching. Instead, as a report from discussions at Basel, headquarters of BiS, indicates most were convinced that no European war would take place.[27]

But we also know that, on the 4th of September 1939, one day after Britain declared war on Germany, Sir Richard Hopkins,[28] a seasoned public servant with a sharp mind, contacted Norman to inform him of the fact that Britain was no longer “bound to observe in wartime the full immunities enjoyed by the BiS.” (BoE, p. 1295). While Norman declared that he would follow that, should it become the government’s official position, he also felt the need to point out that “the proposed attitude of the H.M. Government would doubtless be a surprise to neutral States and would offer hostile propaganda an excellent opportunity for the criticism that […] the HM Government did not hesitate to disregard their international arrangements” (Ibid, p. 1295). In other words, even after Britain had declared war on Germany, Norman continued to hold the same line. Along with the letter, he also included a short memorandum with his suggestions on how to deal with the BiS from that moment on – which was essentially another call to stay put. Ignoring these suggestions, Hopkins wrote back to inform Norman that the Chancellor had decided the following:

- That the BoE should not act upon an order of the BiS if it seems to the BoE to be likely that the order might benefit the enemy.

- That the BoE should not act upon an order without consulting the Treasury.

- That the Treasury will not authorise compliance with an order unless satisfied that it is not likely to benefit the enemy.

- That the present order is subject to enquiry to see what the BiS are prepared to say as to the ownership.

- That neutrals are to be assured that in any case where the Treasury are satisfied with ownership, order by the BiS shown to be on behalf of neutrals will be authorised.

Norman was unhappy, but forced to comply. When another request for a transfer was made 5 weeks after war had been declared, the Governor of the BoE nonetheless went to receive instructions from Chamberlain. In a meeting attended by Chamberlain, Hopkins and others, the decision was made that “the state of war overrides political considerations” (Ibid, p. 1297). That statement seems to imply that the relaxed attitude so far was in fact the result of political considerations, rather than some depoliticized adherence to rule-abiding. The decision was immediately sent by telegram to the pleased French authorities. Nonetheless, the BiS continued to hold meetings with directors from different countries (including fascist Italy) under the pretence of being “strictly impartial and neutral”, a position upheld by Beyen’s replacement, the American McKittrick.

In the end, it was the US entry into the war in December 1941 which increased the pressure towards the BiS and its officials who continued to operate as if general discussions and meetings with all members (including Italy and Germany) were not only possible, but desirable. Voices within the British Treasury were also increasingly pushing towards an understanding that “the only way of not being outwitted after the war by the defeated Germans is to cut our connection with the BiS now” (Ibid, p. 1299). In the end, however, it was growing US hostility towards the BiS that changed the situation. As a member of the American Treasury Department argued, the BiS was not neutral, as it claimed, but German-controlled, adding that continued relations with the BiS had brought about a situation where “there is an American president doing business with the Germans while our American boys are fighting Germans” (Ibid, p. 1301). The name of this outspoken Treasury member was Harry Dexter White. His hostility towards the BiS would remain unchanged until the end of the war and would resurface during the July 1944 Bretton Woods negotiations: his direct proposal was that the BiS should be liquidated “at the earliest possible moment”. It was not.

Marsh, David (1992) The Bundesbank: The Bank that Rules Europe, Random House Publishing; Mee, Simon (2019) Central Bank Independence and the Legacy of the German Past, Cambridge University Press ↩︎

Tooze, Adam (2006) Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy, Penguin. Schacht’s Mefo Bills scheme meant that armament contractors were paid in IOUs issued in the name of the front company Mefo GmbH. This shadowy company, as Tooze (2006: 54) reminds us, “was formed with a capital of one million Reichsmarks, provided by the Vereinigte Stahlwerke, Krupp, Siemens, Deutsche Industrie Werke and Gutehoffnungshütte (GHH)”. ↩︎

James, Harold (1999) ‘The Reichsbank and the Economics of Control’, in Fifty Years of the Deutsche Mark: Central Bank and the Currency in Germany since 1948, edited by the Deutsche Bundesbank, p. 35 ↩︎

One month after the Reichsbank memorandum, a group of economists working under the auspices of the Akademie für Deutsches Recht (created by Hitler’s lawyer and future ‘chief jurist’ of occupied Poland, Hans Frank) put their names in an official memorandum on Kriegsfinanzierung (financing the war). Published 8 months after the nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia and 3 months after the invasion of Poland, the Kriegsfinanzierung plan followed in the footsteps of the Reichsbank memorandum. Rejecting the prevalent view that the war could be financed through “money creation” at a time of fixed prices (a process that according to them led to a dislocation of economic activity and suppressed inflation), the professors proceeded to suggest a more suitable way for funding the war machine: “War should only be financed by financed through taxes and bonds. The only thing to be decided is the proportion in which these two means of financing can be used [...] We are fully aware that the proposed path requires determination in the implementation of measures that must be perceived as tough. However, it is suitable for averting even greater hardship for the people” (‘Professoren-Kriegzfinanzierunggutacthen’, 9.12.1939, reproduced in Möller (1961) „Zur Vorgeschichte der DM: die Währungsreformpläne 1945-1948”, Kyklos Verlag, Basel, pp. 37, my translation. Among the economists who signed this memorandum we find many prominent German neoliberals like Walter Eucken, Adolf Lampe and Heinrich von Stackelberg – a member of the SS at the time. ↩︎

The 1937 Law officially replaced the (in)famous 1922 Autonomy Act of the Reichsbank, legislation that was imposed on a defeated Germany by the Allies, and which reflected the contemporaneous promotion of central bank independence by the League of Nations, its monetary conferences (Brussels 1920; Geneva 1922), Montagu Morgan (Bank of England) and Benjamin Strong (Fed), as well as various other ‘money doctors’. See Do Vale, Adriano ( 2021) ‘Central bank independence, a not so new idea in the history of economic thought: a doctrine in the 1920s’, The European Journal of the History of Economic Thought, Vol. 28.2021, 5, p. 811-843 ↩︎

As Mee writes, “In January 1933 [...] new legislation was passed revising the Bank Act of 1924. The legislation, coming into effect in October 1933, helped to restore the state’s grip on the central bank’s personnel. The general council was abolished. In its place, the country’s president could now appoint the Reichsbank’s president, after hearing the expert opinion of the directorate. The central bank president, for his part, could in turn nominate directorate members who were then appointed by the Reich’s president. Legally speaking, however, the Reichsbank was still independent of government instruction – although such legal independence soon meant little in what emerged to be a totalitarian dictatorship.” Mee 2019: 68 ↩︎

According to a telegram sent to Morgenthau on February 14th 1939, Emil Puhl was “the only one of Schacht’s higher officials who is still in the Reichsbank”, Morgenthau Diaries, Book 164, p. 320. ↩︎

In a special report titled “The Hidden Gold-Reserve Program Initiated by the German Reichsbank during Schacht’s Second Term of Office”, the Division of investigation of Cartels and External Assets of the OMGUS noted: “The purposes of this program are not fully clear, but testimony of the officials questioned has revealed that one of the most important accounts involved was, as least as early as 1937, referred to by officials of the bank as their war reserve. Those questioned agree that the Treuhandgesellschaft account, created by Schacht late in 1935 and amounting to more than twice the published reserves at that time, came to be known by a sort of slogan within the bank as their “new Juliusturm” – a reference to the gold reserve built up for the last war and stored in the Julius Tower in Spandau”. Declassified E.O. 12065 Section 3-402/NNDG, No. 775059, p. 2, Institut für Zeitgeschichte (IfZ), Munich. ↩︎

Three days after the July 1944 assassination attempt against Hitler, Schacht was arrested on suspicion of having had contact with the conspirators and sent from the Gestapo prison of Berlin to the Ravensbrück and Flossenbürg concentration camps, ending up in Dachau in April 1945. He was liberated a few weeks later by the American army. ↩︎

Cited in Mee 2019: 78, ↩︎

As Oswald Pohl, one of Himmler’s chief assistants and one of the few to be executed after the Nuremberg trials would say, “the members of the Circle of Friends were picked, politically reliable and loyal people; otherwise they would not have been invited by Himmler”. As the potential for a military victory was becoming less likely, many of the ‘friends’ stopped attending the meetings. In 1943, an SS loyal member sent an angry letter to Himmler complaining about the situation, keeping a record of the absentees and praising “those gentlemen who [...] were honestly and cheerfully making every effort to attend all our meetings”. Blessing was among them. Both citations from the official investigation into Karl Blessing by the Investigations Branch, Finance Division of the Office of the Military Government of the US (OMGUS), Declassified E.O. 12065, Section 3-402/NNDG, no. 765035, Institut für Zeitgeschichte (IfZ), Munich. ↩︎

“Interrogation of Hjalmar Schacht”, Investigations Branch, Finance Division, of the Office of the Military Government of the US (OMGUS), Declassified E.O. 12065, Section 3-402/NNDG, no. 765035, p. 9, Institut für Zeitgeschichte (IfZ), Munich. ↩︎

Do Vale (2021) ↩︎

Cited in Cottrell, P. L. (1997) “Norman, Strakosch and the Development of Central Banking: From Conception to Practice.” In Rebuilding the Financial System in Central and Eastern Europe, Aldershot: Scolar Press, p. 33 ↩︎

Hawtrey, R. G. (1928) “Central Banks.” The Economic Journal, 38 (151), p. 439. doi:10.2307/2224322. ↩︎

Cottrell (1997), p. 48 ↩︎

Sayers, R. S. (1976), The Bank of England 1891–1944. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 154-55. ↩︎

Feiertag, O. (1999) “Banques centrales et relations internationale au XXe siecle: le probleme historique de la coopération monetaire internationale».” Relations Internationales 100: p. 364, cited in Do Vale (2021), p. 14 ↩︎

Do Vale (2021), p. 6 ↩︎

James, Harold (2001) The Deutsche Bank and the Nazi Economic War Against the Jews, Cambridge University Press, pp. 26, 58. ↩︎

“Montague Norman [...] has always stood, in season and out of season, for an understanding with Germany and has always regarded as inevitable the unification of the Germanic parts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire with Germany", Morgenthau Diaries, Book 159, p. 69. ↩︎

In his interrogation in 1945, Schacht described Funk as someone who is “certainly stupid and in fact has no knowledge of finance.” Op.cit. “Interrogation”, p. 14. ↩︎

As the Financial News wrote at the time, “presumably Dr. Schacht’s dismissal will be followed by a series of radical economic and financial measures. The sanctity of private property and the capitalist character of the German economic system will probably be further attacked by means of new confiscatory measures”. Morgenthau Diaries, Book 162, p. 12 ↩︎

The BiS was created in 1929 to oversee the World War I reparations owed by the German government as agreed in the Young Plan. Among those who participated in the expert committee that created it was Schacht himself. He only left the board in 1939 after his dismissal from the Reichsbank. ↩︎

Beyen would later play a key role in the process of European integration. ↩︎

The Bank of England 1939-1945, Unpublished War History, Part III, Chapter IX, p. 1293, available here. ↩︎

“Practically all of my central banking contacts are convinced that there will be no European war, although they expect this year to be marked by incidents of an unpleasant and perhaps upsetting character. It is very encouraging for them to see the liquidation of the Spanish civil war which is now underway. International wars, they think, are more likely to follow a period of prosperity than of depression”. Morgenthau Diaries, Book 169, March 1939, p. 151 ↩︎

Controller of Finance and Supply Services (1927-1932), head of Treasury (1942-1945), Sir Richard Hopkins was a seasoned public servant with a sharp mind and a taste for practical, new ideas. In 1929, he defended the so-called ‘Treasury view’ in front of the Macmillan Committee. The ‘Treasury view’ was developed in opposition to the views of Lloyd George and JM Keynes who supported that a “loan-financed” public works program was capable of bringing unemployment from 10-11 to 5-6 per cent within a year. Cross examined by Keynes himself during one of the committees’ sessions, Hopkins essentially argued that though there was some evidence that such a scheme would help with unemployment figures, its adoption would set a dangerous precedent of ignoring a balanced budget orientation and the unspoken rule that government expenditure should be sanctioned when it brings a profit. Geared towards increasing competitiveness with an eye on world markets and not on domestic demand, Hopkins would uphold the ‘Treasury view’ despite Keynes’ objections. It was not until 1945 that Hopkins was prepared to accept Keynes’ fundamental inversion of the Treasury View which held that it was saving that determined the level of investment and not vice-versa. But even before that, the achievement of full employment during the war years had convinced both Keynes and Hopkins that there was dire need for a new employment policy to be sketched out. For this reason, Hopkins is credited with intervening for reinstating Keynes as an advisor to the Treasury. By 1944, and after various draft versions of an original paper by James Meade were discussed in a committee chaired by Hopkins, a Keynesian view was adopted and fully backed by Hopkins. Keynes called it a “revolution in official opinion”. See Peden, GC (1983), ‘Sir Richard Hopkins and the “Keynesian Revolution” in Employment Policy, 1929-1945, The Economic History Review, Vol. 36, No. 2 (May, 1983), pp. 281-296. ↩︎

Sign up for Notes on the Crises

Currently: Comprehensive coverage of the Trump-Musk Payments Crisis of 2025