Trump’s “Liberation Day” and the Ongoing Stock Market Crash: The Key Lessons to Take into the Second Week of the Market Bloodbath.

Read Part 0 , Part 1 , Part 2 , Part 3 , Part 4 , Part 5 , Part 6 , Part 7 , Part 8 , Part 9 , Part 10 , Part 11 , Part 12 , Part 13 , Part 14 , Part 15 , Part 16 , Part 17 , Part 18 & Part 19.

Hello readers, apologies for my extended absence. It has been a little more than three weeks since my last piece, simultaneously published by Notes On The Crises and Rolling Stone, assessing the extremely alarming implications of the Federal Government taking 80.5 million dollars right out of New York City’s bank account. This temporary hiatus came out of a large set of background organizational and investigative reasons. The organizational reasons include some exciting expansion of Notes on the Crises which I will be able to go into detail about soon. While I will have updated on payments system issues later this week, some of the most challenging aspects of my investigative reporting are still ongoing. Thank you for bearing with me and stay tuned: I think you’ll find that what I have coming is worth the wait. Of course, I have a lot to catch up on…

The extensive “Notes on the Crises Investigative Journalism Source Wish List” can be found here. All listed items are important to me. As always, Sources can contact me over email or over signal (a secure and encrypted text messaging app) — linked here. My Signal username is “NathanTankus.01” and you can find me by searching for my username. I will speak to sources on whatever terms they require (i.e. off the record, Deep Background, on Background etc.)

This is a free piece of Notes on the Crises. I will not be paywalling any coverage of this crisis for as long as it persists, so please take out a paid subscription to facilitate performing that public service. You can also leave a “tip” if you want to support my work but hate emails cluttering your inbox or recurring payments. If you’re rich, take out the Trump-Musk Treasury Payments Crisis of 2025 Platinum Tier subscription.

Note to Readers: I am on bluesky, an alternative to twitter. I have also started an instagram for Notes on the Crises which is currently being populated with my articles.

Finally, I'm known as a crypto skeptic, and I am, but that doesn't mean I won't accept people giving away bitcoin to me. Here's my address: bc1qegxarzsfga9ycesfa7wm77sqmuqqv7083c6ss6

Despite the multitude of payment system related reporting I need to bring to readers, much of which is already written, I’m actually going to start my renewed coverage with the most recent news: the Tariffs.

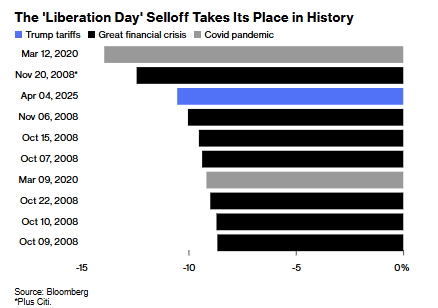

This is for a few reasons. For one thing, the stock crash late last week was absolutely enormous. The one day and two day crashes are only comparable to Covid, the 2008 Great Financial Crisis crashes and the 1987 stock market crash. Before putting the finishing touches on this piece and going to bed, I watched Bloomberg news from midnight to 1:30 AM and these comparisons were repeated over and over. At 1:00 AM a Bloomberg anchor summarized the situation by saying "Carnage, panic, bloodbath does not even cover it". Meanwhile, the crash last week is not over, it only paused for the weekend. As of this writing, the stock market “futures” markets are already crashing. John Authers in his Bloomberg newsletter reported at 1:00 AM “If the 4.8% fall in S&P 500 futures at the Asian opening isn’t reversed, then it’s on course for its worst three-day selloff since the Black Monday crash of October 1987.” This is, to say the least, not a good sign.

But let's back up to the very basics to explain what any of this stuff even means. Bear with me as I (briefly!!) start at the very beginning. First things first: “stock markets” are not just abstractions to talk vaguely about capitalism, large corporations or the wealthy. Stock markets are actual, concrete institutions. The main stock market in the United States, the New York Stock Exchange, is reputed to have informally begun as what today would be called a “cartel” of 24 stock market brokers organized by the “Buttonwood Agreement” on May 17th 1792. The New York Stock Exchange’s website neatly summarizes subsequent developments:

In the Exchange’s early years, stock trading continued on an informal basis in nearby coffeehouses where merchants typically gathered. By 1817, the stock market was active enough to encourage the brokers to create a formal organization. A constitution was adopted on March 8, 1817, creating the New York Stock & Exchange Board, the forerunner of today’s NYSE. From the beginning, regulations governed trading.

This is the very meaning of “market open” and “market close”. The New York Stock Exchange literally has an opening time— 9:30 AM— and a closing time— 4:00 PM Est. The other major U.S. stock exchange is the “Nasdaq”, which follows the New York Stock Exchange’s opening and closing time.

So that’s stock market basics. But wait: what are “S&P 500 futures”, and what do they have to do with the stock market and how are they already trading if U.S. stock markets don’t open until 9:30 AM? Those of you who are invested in the stock market (sorry!) probably have some idea what the “S&P 500” actually means. A company called the “Standard & Poors Company” publishes an index of the 500 “largest” stocks”. “Largest” in this context means the total “market value” of all the stocks that company issues. Index funds in turn list something called “Exchange Traded Funds” which track the indices produced by “index providers”. I know this has gotten complicated fast, but the only way out is through.

To summarize, some entities publish indices saying “hey I’m summarizing what’s going on with all stocks, or a certain type of stocks, with this one number! If it goes up, good! If it goes down, bad!” and index funds come along and say “oh great! We’ll sell people a product that’s whole job is just tracking your index and we’ll pay you a fee for using your intellectual property [yes, really]. We’ll charge our customers a little fee for buying and selling assets to make sure our holdings follow your index!” In this way, individual financial products are produced which “encapsulate” what’s going on with the stock market.

Intrepid entrepreneurs started approaching stock exchanges around the world and going “hey, wouldn’t it be great to have a guess at what’s happening with U.S. stocks when your markets are open and U.S. markets are closed?”. You may have heard the term “derivatives”. It may sound scary but at the most basic level, the concept is simple. A financial derivative is just a type of financial asset that’s value is “derived from” or “derivative” of another financial asset. In the case of “futures markets”, what they trade are contracts which promise to deliver another asset at a specified date.

Bringing this all together, the phrase “4.8% fall in S&P 500 futures” means that contracts which promise to deliver Standard & Poor 500 tracked “Exchange Traded Funds” (ETFs) issued by index funds went down in value by 4.8%. The “on Asian stock markets” part of John Authers sentence references that the S&P futures contracts he was looking at were trading on stock exchanges in Asia. The Japanese stock market, for example, opens at 8 PM Est. the “previous day”. These interlocking exchange listed financial products provide a way of speculating on gaining insight into the behavior of U.S. stocks before the New York Stock Exchange and Nasdaq open.

I’ll have way more to say about stock & commodity exchanges —and index funds—in the future and have been meaning to write way more about them for a long while. A paper I co-wrote with Luke Herrine, who is now a law professor at the University of Alabama, in 2021 has an extended discussion of commodity and stock exchanges. That paper was published the following year as a chapter in the “Cambridge Handbook of Labour & Competition Law”. I also wrote a piece in September 2020 entitled: “The Stock Market Is Less Disconnected From the ‘Real Economy’ Than You Think: Stock Market Indices Aren't The Stock Market” —well worth reading in this context.

In my description above, I skipped over a crucial bit: Standard & Poors using the total value of a company’s stock as a basis for including companies means that stocks which skyrocket in value in a relatively short period of time may skyrocket their way into these indices. What happens then? This is no hypothetical. In December 2020 I had a guest piece by three European economists, Johannes Petry, Jan Fichtner & Eelke Heemskerk, which opened with an example which reads even more extraordinary and prescient than it did at the time:

Over the course of 2020, Elon Musk’s wealth skyrocketed from $27.7 billion to $147 billion. Musk even overtook Bill Gates, to become the second richest person in the world. This was a tremendous jump in fortune: Musk was only at 36th place in January 2020. Musk’s enrichment was mainly due to Tesla’s rising stock price (TSLA:US), which surged from $86 in January to $650 in December. Tesla is currently one of the ten most valuable companies in the US stock market.

In an already record-breaking year, Tesla’s largest and most rapid increase in valuation came in November, due to its announced inclusion into the S&P 500 index, now scheduled for 21 December 2020. Within a week of this announcement, Tesla’s share price rose by 33%, as passive funds now have to invest more than $70 billion. This was a remarkable boost for stock of a company that many analysts say is already obviously overvalued.

In a very real sense, Donald Trump may have become president and Elon Musk may have taken the reins over the key infrastructure in the federal government, setting off the Trump-Musk Payments Crisis, simply because index funds exist and the 2020 jump in Tesla’s stock price led to Tesla’s inclusion in indices like the S&P 500. Try not to think about it too much.

Finally, Some Actual Tariff Commentary

By now I’m sure some readers are impatient for some actual tariff talk in this piece that’s allegedly about Trump’s tariffs. Here’s the tariff talk you’re looking for. As readers know, tariffs have been a constant topic for months. Since the first week of the Trump-Musk Treasury Payments Crisis I’ve been asked over and over about tariffs. My informal answer has been that the tariff news, as important as it was, was so much less important than what was happening in the payments system that it was not worth taking time to cover. This was especially the case since plenty of people were covering tariffs—but vanishingly few are covering the payments issues. That’s in large part because so few people who write week to week news coverage understand these complex and understudied payments issues.

I still think, as insane and dangerous as these tariffs are, that the tariff story is still less important and less dangerous than what is happening on the payment system side of the Trump administration’s chaos.

Talking about tariffs is worth it just to make this bold claim because I’m sure for many readers it will make my concerns about the payments system concrete. Hopefully this will serve as a measure for readers to evaluate how enormously alarmed the payment system issues make me (and the experts I talk to) two months on. Tomorrow I will have another piece discussing why the stock market is crashing now—but hasn’t crashed over the Trump-Musk Payments Crisis (yet!)

On the tariffs themselves, the issues are pretty straightforward to me. Longtime Notes on the Crises readers know that one of my earliest and most persistent concerns during the onset of the Covid depression was that, despite the rapid decline of economic activity, there were going to be large economic dislocations because of supply chain disruptions. This meant there was a challenge between increasing demand for the specific goods and services people needed in the pandemic, especially those laid off and living on unemployment benefits, versus making sure supply chains could keep pace.

Rather than talk about these issues in terms of “supply and demand”, my focus has always been the interdependent set of economic activities that keep a global economy going. Once you consider how reliant any individual area of economic activity is on every other part of economic activity through an incredibly complex web of inputs and outputs, it becomes more difficult to believe that there is something called “supply” which is conceptually independent or coherently separable from something called “demand”.

What does this all have to do with tariffs? Well, the Trump tariffs are remarkable because of the combination of the way they are being introduced, as well as the extremity of the tariffs (or more frankly: insanity). They were literally generated by an AI chatbot which was asked for an “easy” way to calculate tariff rates. The Washington Post reported that the “AI chatbot” option was personally chosen by Trump less than three hours before Trump went onto the White House’s Rose Garden to announce the tariffs. In essence, his “Liberation day” Tariffs have created a supply chain crisis for the United States comparable in speed and scale to the global pandemic which shut down the world five years ago. It’s important to step back and process that statement and just how remarkable it is.

It is remarkable because what we are talking about is not an external event or a biological or environmental disaster. It is the straightforward consequence of Donald Trump’s election, who was quite clear that he would be imposing sweeping tariffs in the wider context of sweeping promises of erratic vengeance on his enemies during a second term. As a rule, neither recessions or booms are the result of the individual preferences or predilections of individual presidents. Trump is breaking this rule, just like he’s broken so many others.

Nearly five years ago I published a piece in this newsletter entitled “What are the Three Concurrent Crises of the Coronavirus Depression? The Keynes Crisis, The Minsky Crisis and the Means Crisis”. The “Means crisis”, named after the economist Gardiner Means, was the physical allocation of goods and services and the need for their rapid reorganization. This was inspired both by Gardiner Means’ theoretical work and his practical work at the New Deal era agency “The National Resources Planning Board”. It is worth quoting my description of the importance and implications of a Means crisis:

Existing prices and existing patterns of production and consumption can be sustained relatively easily by private action. However, profit-seeking businesses are bad at reallocating resources in response to crises. The uncertainty of how long the crisis will last and whether the costs of retooling plants and restructuring supply chains can be recouped discourages bold action. It is often perceived to be cheaper to simply leave productive resources unused than go through such expenses and uncertainties. Even farms are letting crops rot and euthanizing animals rather than trying to find ways to reorganize their supply chains. What Means work teaches us is that the government should step into this breach. It should be directly physically reallocating resources and organizing production through hiring workers and guaranteeing private producers markets. Resources left unplanned, are predictably unorganized. Private Sector planning works at dealing with medium and long term resource questions but struggles to move quickly and effectively in times of crisis. [emphasis added]

Of course, in our current circumstances a chaotic and destructive government is the crisis. So that can’t be a solution. Collective action from ordinary people (or elites) is needed to first force the Federal Government to roll back its destructive policies. Then we need collective action to defeat this government entirely. Necessity, however, should not be confused with likelihood.

To make this discussion concrete, the stated intention of Trump’s tariffs is to lead to higher domestic production of “tradable” goods and services. As Trump said on “National Liberation Day” (I’ve uploaded a pdf of a transcript of his remarks to my website for ease of access and posterity):

With today’s action, we are finally going to be able to make America great again, greater than ever before. Jobs and factories will come roaring back into our country, and you see it happening already. We will supercharge our domestic industrial base. We will pry open foreign markets and break down foreign trade barriers.

This can work in two ways. First: multinational corporations can decide to shut down production plants abroad and shift production domestically. This requires lots of upfront economic resources. Put simply, it takes large expenditures of money to buy production inputs and hire labor to build new factories. Meanwhile, building new factories takes time. Specifically, it takes years.

The second way, on the surface, seems more straightforward. This is called “expenditure switching”. In simpler terms, businesses and households choose to buy the same goods and services they would buy from other countries from existing domestic sellers. In this vision, underutilized capacity gets utilized. Trump doesn’t seem to be putting much stock in this option. In his Rose Garden remarks Trump said:

But what you’re going to see is you’re going to see activity that empty dead sites, factories that are falling down. Those factories will be knocked down, and they’re going to have brand new factories built in their place. They’re not only talking about renovating, they’re talking about brand new, the best anywhere in the world, the biggest anywhere in the world

Whether a new factory is being built because a company is shutting down production abroad or simply expanding production domestically, it still involves a lot of upfront economic resources.

A lot of people have been praising the merits of free trade in response to Trump’s tariff actions. This is understandable, but misses the point. None of this has anything to do with protectionism. It’s about exercising crude, coercive power abroad just like the Trump-Musk Payments crisis has been doing domestically. An industrial policy strategy aimed to develop domestic manufacturing would be focusing on a handful of higher value products. It would probably focus on high value final products i.e. those sold to consumers. Maybe a few key industrial inputs. They would also likely focus on just a few countries.

Instead, Trump’s tariffs are targeting the entire world; Including uninhabited islands of Penguins. They are also targeting all products, including a sweeping list of agricultural products that we will largely not be producing in the United States under any circumstances. The closest comparison we have for these tariffs in U.S. history are the 1828 tariffs that were branded “the Tariff of Abominations”. Trump’s tariffs make those nearly two century old tariffs look like one of the most brilliant development strategies ever undertaken.

The upshot of all this is that it would not be hard to imagine 6 or 8 industries advancing now that they can either charge higher prices or gain market share at the expense of foreign businesses. Instead, economic uncertainty is exploding and nearly every business in the country has no idea how much their costs will rise, how far their sales will fall or if they will even be able to get new inputs. It's not just that the costs of a business’s inputs are being tariffed at the same time that a business's industry is receiving “tariff protection”. It's also that a whole series of domestically produced inputs are also impacted by tariffs to an extent that you can’t predict. Will your costs go up 20%, 70% or 120%? You do not know. What are the impacts on your costs from all the businesses six degrees separated from you raising prices because of the tariffs they are experiencing?

This is the supply chain problem I was talking about. Tariffs have been slapped, to an unpredictable degree, all across the supply chain and it will take months to sort out the impact if they don’t get rolled back. Months of businesses and households waiting around and avoiding expenditures to learn more about what will happen are the months that will sink the global economy. To the extent president Donald Trump has really thought about any of this, he clearly is having some version of the thought process “tariffs are good, they will bring manufacturing back, more tariffs implemented more quickly will bring manufacturing back faster and bigger”. Instead he has set off thousands of sudden physical resource allocation problems, cost problems and more.

Who in their right mind would commit to large scale projects building brand new U.S. factories right now? Especially since the escalating sense of chaos opens up the possibility that the tariffs will be moved back down and you’re now caught making investment decisions based on numbers written on an Etch-a-sketch. And indeed, that’s exactly what we’re seeing. Trump wants a manufacturing boom and instead he’s stoking a global recession and causing supply chain paralysis. It's truly amazing to witness.

Which leads to the final point. What truly makes this crisis remarkable is it’s hard to see what will come to the rescue. In 2008 and 2020, central banks cut interest rates and deployed large programs. Congress passed the CARES act in 2020. Republicans are currently in a strong austerity mood- that’s a major part of the ideological background for the entire Impoundments crisis. Meanwhile Fed chairman Jerome Powell and the Federal Reserve are skittish from all the criticism they faced for not raising interest rates “soon enough” after 2021. This is worsened by the fact that the price increases that will come with the tariffs dissuade strong Federal Reserve action. Put simply, the Fed will be extraordinarily reluctant to cut rates if they expect “persistent inflation” from here on out. More fundamentally, monetary policy simply does not have the tools- even with extremely audacious use of the Federal Reserve’s “emergency” authority- to patch up the results of an out of control executive branch unconstitutionally creating volatile “discretionary” fiscal policy tools for itself.

At the time of this writing at 2:00 AM Est., the consensus of financial commentators seems to agree with me. So do financial traders who are betting on remarkably small interest rate cuts relative to the scale of the economic calamity their stock market bets illustrate.

The good news is that there are signs that business elites in this country are finally turning on Trump as a result of all this. With one of the greatest stock market crashes in world history, the odds of American democracy surviving Donald Trump and Elon Musk have gone up. If only it didn’t cost so much. More on this, tomorrow.

Sign up for Notes on the Crises

Currently: Comprehensive coverage of the Trump-Musk Payments Crisis of 2025